Spotlight on Innovation

The Technology Review Custom Team takes a look at the technologies that are changing the ways in which we do business in the clean energy, life sciences, infotech and homeland security clusters.

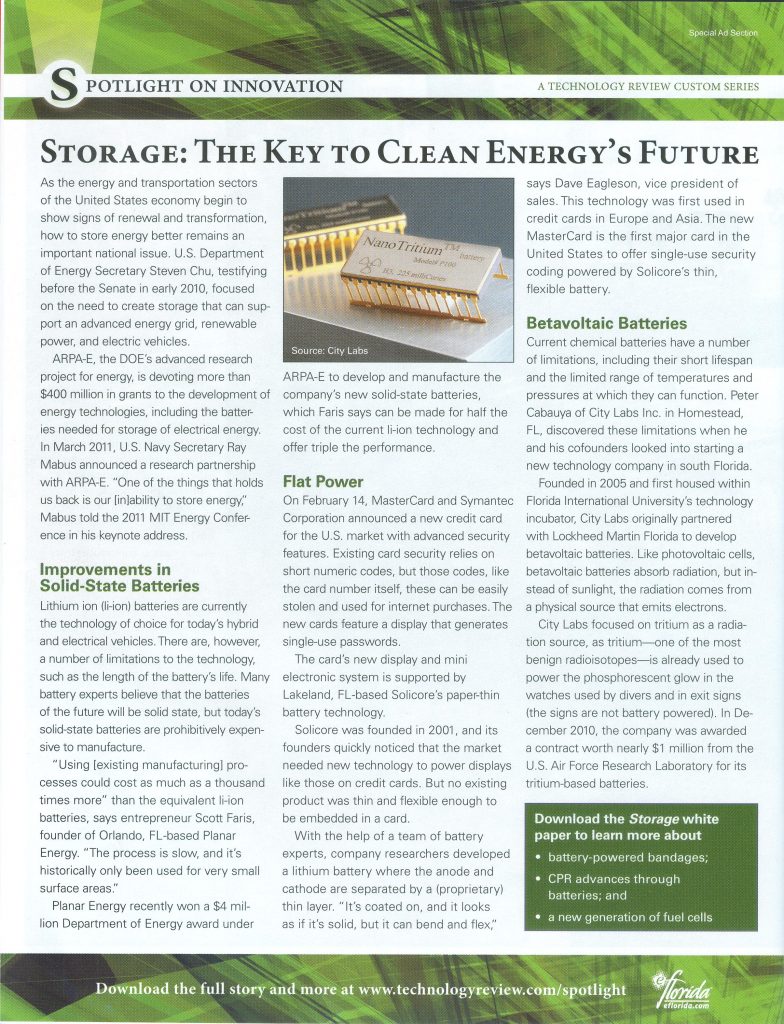

Betavoltaic Batteries

Current chemical batteries have a number of limitations, including their short lifespan and the limited range of temperatures and pressures at which they can function. Peter Cabauy of City Labs Inc. in Homestead, FL, discovered these limitations when he and his cofounders looked into starting a new technology company in south Florida.

Founded in 2005 and first housed within Florida International University’s technology incubator, City Labs originally partnered with Lockheed Martin Florida to develop betavoltaic batteries. Like photovoltaic cells, betavoltaic batteries absorb radiation, but instead of sunlight, the radiation comes from a physical source that emits electrons.

City Labs focused on tritium as a radiation source, as tritium—one of the most benign radioisotopes—is already used to power the phosphorescent glow in the watches used by divers and in exit signs (though the signs are not battery powered). In December 2010, the company was awarded a contract worth nearly $1 million from the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory for its tritium-based batteries.

Betavoltaic Batteries

Current chemical batteries have a number of limitations, including their short lifespan and the limited range of temperatures and pressures at which they can function. Peter Cabauy of City Labs Inc. in Homestead, FL, discovered these limitations when he and his cofounders looked into starting a new technology company in south Florida.

The founders researched the federal government’s small business innovation research grants and discovered an unmet need for a long-life power source, a battery that supplies small a mounts of power and that can withstand major temperature ranges and last for decades. The military needs such batteries, to take one example, on unmanned aerial vehicles; all information that is exchanged between the base and UAV must be encrypted and the crypto-keys demand the highest class of security. Those keys are backed up on the vehicle, and that backup operates on battery power. Coin-cell batteries have been used in the past, but they fail quickly because of the massive temperature swings that confront a plane that flies at 40 thousand feet and minus 60 °C, and then lands in the desert’s broiling heat.

Though City Labs did not win that particular small business innovation research grant, its company researchers decided to develop just such a battery, based on betavoltaic technology, anyway. Betavoltaic batteries operate via radioisotopes like photovoltaic cells, beta-voltaic batteries absorb radiation, but instead of sunlight, the radiation comes from a physical source that emits electrons.

“In hot, cold, rain, shine, the fuel is always working; it’s always emitting electrons,” says Cabauy. “It can withstand temperature swings and could last for 20 years.”

The idea of radiation-powered batteries has been around since the 1950s, but previous attempts used radioisotopes with high energy, explains Cabauy, and the electrons destroyed the semiconductor. Instead, City Labs focused on tritium as a radiation source, since tritium – one of the most benign radioisotopes – is already used to emit radiation to power the phosphorescent glow in divers’ waters and exit signs (though the signs are not battery-powered).

“[With tritium], the beta electrons are the least powerful, and a sheet of paper could stop them,” says Cabauy. “That’s great for safety, but it’s difficult to get that energy converted in a semiconductor. We had to work on getting the efficiency up.” From 2006 through 2008, the team focused on developing the semi-conductor structure, and then achieved the appropriate regulatory licenses that certify the product’s safety, and are needed to allow anyone, without prior radiation training or licensing, to buy the product.

How much power does a nuclear tritium battery make?

Tritium batteries typically supply power in the nanowatt to microwatt range and can be extended to milliwatts. They are designed to power low-power electronics over long periods of time.

Are tritium batteries safe?

Tritium releases beta particles, which are very weak compared to other forms of radiation. This radioactive decay can be entirely blocked by sheets of metal that are only a tiny fraction of the thickness of a penny. Coating tritium batteries is easy, cost-effective, and makes them safe for commercial and practical uses.

City Labs originally partnered with Lockheed Martin in Florida to develop this technology. Lockheed Martin was interested in its military applications and tested the batteries from minus 50 °C to 150 °C.

In December 2010, the company was awarded a contract nearly $1 million from the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory for its tritium-based batteries.

Beyond military applications, City Labs sees potential medical applications. “One company is looking at monitoring tumor regrowth. Conventional batteries [in a sensor] would have to be implanted every six months, but the tritium battery can last decades,” says Cabauy. The company is currently expanding its manufacturing in the Miami area.