The NanoTritium can travel into enemy territory, plunge to the bottom of the ocean and even settle into the human heart. And it keeps going, even through extreme temperatures and vibration, for 20 years or more.

Just the size of an adult’s thumb, NanoTritium is a different kind of battery — and now it’s available commercially. Homestead-based City Labs, the small high-tech company that created NanoTritium, says it’s the first time such a power source has gone on sale to end-users — most likely companies — that don’t have specialized training or separate regulatory approval. Florida International University alum Peter Cabauy and University of Miami alum Denset Serralta say their low-power battery can be used to run micro-electronics anywhere that’s hard, dangerous or expensive to reach.

Think: sensors on deep-water oil drills, in medical devices implanted into the body, even hidden in a wall in a spy hangout. In fact, the company is already looking at the military applications for its product: City Labs has been awarded a $1 million Air Force contract for a higher-power, customized battery. (Cabauy said he couldn’t discuss specifics of the lab’s military contract.)

“Basically they can be used for items like sensors where you cannot maintain them but you need them to be operating for a long time,” said Serralta, chief technology officer of City Labs.

The device is expected to be valued in the “couple thousand dollar range” at first, Cabauy said, but the price should go down as the company produces more of the devices.

What makes the NanoTritium so resistant and long-lasting is the way it’s made. This is a betavoltaic power source, meaning it’s powered by a radioactive element. Whereas normal batteries are powered by chemical processes, the NanoTritium is powered by physical processes of one of the most benign radioisotopes: tritium.

Another way to think about betavoltaics is to think of a solar cell, said University of Miami Professor Joshua Kohn, a materials physicist, who is not involved in the project. But instead of absorbing photons from the sun to create energy, betavoltaics absorb radioactive particles, he said.

Kohn called the idea of a commercially-available betavoltaic “intriguing.”

“I’m skeptical it will be a market-maker, but it certainly has some niches it could fill,” he said.

“It’s an old idea that goes back to the 50s and 60s, and I guess it was abandoned back then because they had to use a more dangerous material, ” he said.

That’s not an issue with tritium, which is already used to make exit signs and divers watches glow. The electrons it emits can be stopped by something as flimsy as a sheet of paper.

“If you go on the Metrorail, I counted about 100 [exit] signs through all the stations. And they [each] have, oh, about 20 times the amount of tritium [as the battery], and it’s in gaseous form,” said Cabauy, CEO of City Labs.

The tritium in NanoTritium is solid, “so even if this gets broken or punctured, it all stays inside,” he said.

UM’s Kohn said low-power batteries are being developed out of many materials, even algae, for all kinds of uses, such as tracking store merchandise.

Cabauy and Serralta didn’t originally set out to create such a battery. With few high-tech jobs available in South Florida, they first set out to create a company that could provide science and engineering students with employment.

“FIU, the University of Miami, they’re graduating thousands of engineers and scientists, and they get out and there aren’t jobs,” said Cabauy, who has a PhD in applied physics from the University of Michigan. “We looked at this and we said, ‘We have to do something. We love Miami. We have to be here.’ ”

Fueled by private investors — including Alex Aguila, co-founder of Dell subsidiary Alienware Corporation — City Labs currently has five full-time employees.

Cabauy lobbied FIU officials to develop the Office of Entrepreneurial Science, which provided office space for enterprising scientists and engineers looking to launch their own businesses.

Next, he and Serralta went looking for a problem that needed solving.

“Being an engineer, scientist, the community starts to talk,” Cabauy said. “We were actively looking for problems that we could solve. So we didn’t fall in love with, ‘Oh we have the technology here for a battery.’ We fell in love with the problem. And we knew that there was a need for long-lived, low-power that can withstand extreme temperatures.”

With a problem defined, Cabauy did what any good scientist would: research. That’s how Larry Olsen, who has a PhD in physics, came onto the scene.

Trolling Spanish online forums, Cabauy read about Olsen’s work on betavoltaic batteries in the 1970s, when Olsen helped created a betavoltaic power source strong enough to power pacemakers. Doctors from Uruguay marveled online that in many cases, the medical devices outlasted the patients. A typical pacemaker, powered by lithium, usually lasts only about 10 years, Cabauy said. That means the patient has to undergo expensive, invasive surgery to replace the device’s battery.

City Labs — which by this time, had begun moving to a business incubator in Homestead — tracked down Olsen and brought him on as a contractor at first, and later pulled him out of retirement to become the company’s director of research.

“The idea intrigued me,” Olsen said. “When this came up, it really was an exciting possibly.”

Olsen’s battery never became mass-produced because lithium batteries came on scene shortly after his was invented. Olsen also was using a more radioactive element, which meant its encasing needed to be bulkier to make it safe.

Since Olsen’s work in the 1970s, the power needed to run devices has gone down dramatically, he said, making products like the NanoTritium possible. City Labs’ battery produces nanowatts of power, which means it isn’t strong enough to power a cell phone or laptop.

It took Olsen’s expertise, money scrapped together from family, friends and investors, years of research and volumes of regulatory paperwork to develop the NanoTritium.

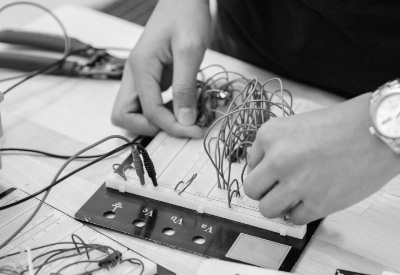

The battery is only currently available in “engineering” quantities — up to 1,000 a year, Cabauy said. They’re assembled in the company’s small Homestead lab, where the ventilation system rumbles non-stop.

“I think the time is right,” Olsen said. “What we’re doing, I think, is really quite viable.”